Jessica Cejnar Andrews / Thursday, Sept. 1, 2022 @ 1:10 p.m.

Online Auction of Yurok, Hoopa Basket Caps Sparks GoFundMe Campaign

Alanna Lee Nulph was angry.

The Yurok Tribal member had found 80 “Northwest California basketry hats” on Bonham’s Auction House. Nulph, who, along with a coworker, scours the Internet searching for regalia belonging to her people, managed to buy one lot. But, she said, the Encanto Gallery in New Mexico outbid her and then posted the items for sale on eBay.

“If you see some of these, they would buy this whole lot of about three or four caps for about $1,600 and they’ll turn around and sell one cap for $1,600,” she told the Wild Rivers Outpost. “They’re making three times the amount they bid (for) these, and they’re outbidding tribal members.”

To Nulph and her people, these basket caps are family members, loved ones. They’re alive, she says. Though there’s a resurgence in the art, there aren’t many people left who can weave them. Many are fragile, and in some cases, Nulph says, it’s obvious they were taken from a grave.

Nulph voiced her frustrations on Facebook at about 2 a.m. Tuesday. Following her post, Lucas Garcia, a tribal member seeking to represent the East District on the Yurok Tribal Council, started a Go Fund Me campaign. He aims to raise $50,000 to buy the caps from Encanto Gallery and bring them home.

On Wednesday, Garcia told the Outpost he spoke with the gallery owner who wanted to remain private, but indicated that he would be willing to hold the basket caps so Garcia’s Go Fund Me campaign could raise the money needed to purchase them. According to Garcia, the owner didn’t understand the cultural significance of the caps and thought they were made with the intention of selling them.

“He said he appreciated the basketry and the intricate designs that are on them and he said, ‘Hey, I can make a little bit of money off of this,’” Garcia told the Outpost. “He definitely appreciated me reaching out to him and coming in a good way, manner, more in an educational approach rather than trying to cancel the gallery itself — trying to shut them down.”

Since Nulph’s post, the Encanto Gallery has shut down its Facebook and Instagram pages, its website is blank and its phone number has been disconnected.

According to Garcia, the gallery owner is asking for $45,000 for 39 caps. He said if he’s able to bring them back home, he’d like to create a space for them and potentially loan them to tribal members during ceremony unless they can find a “paper trail” leading to those who actually did own them.

Garcia said he hoped to get Rose Clayburn, the Yurok Tribe’s historic preservation officer, involved and, potentially the Hoopa Valley Tribe, whose museum loans cultural regalia out for ceremonies. He mentioned the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), but said he wasn’t sure if that would apply because these are items held in private collections and being auctioned off by private sellers.

Passed in 1990, NAGPRA provides a process for federal agencies and museums to return Native American cultural items including human remains, funerary and sacred objects and items of important significance to Indian tribes and Native Hawaiian organizations and lineal descendants.

Any institution, state or local agency receiving federal dollars must comply with NAGPRA. That typically doesn’t include private collectors, though last year the End of the Trail Museum, part of Klamath’s Trees of Mystery, faced some scrutiny since it received federal CARES Act money, Indian Country Today reported in May 2021.

Trees of Mystery received three federal Small Business Administration loans totaling $650,000 related to the pandemic. The End of the Trail Museum houses an extensive collection of cultural items collected by the attraction’s founder, Marylee Thompson.

Nulph said she and several of friends coordinate with each other when they bid on tribal items they find via online auction sites in an effort not to drive the price up. It’s the “wild west of repatriating items right now,” she said.

There’s no coalition or inter-tribal agreement focusing on acquiring cultural items from private collections, Nulph said. If tribes are able to repatriate items, she said, the effort is often tied to a grant and is very specific.

“There are other items every once in awhile that will go up for bid,” Nulph told the Outpost. “I know there was a Jump Dance basket that a year ago sold for $16,000 and I know another tribal person got that. Sometimes it’s bowls. Sometimes trinket baskets — I’ll see all kinds of stuff.”

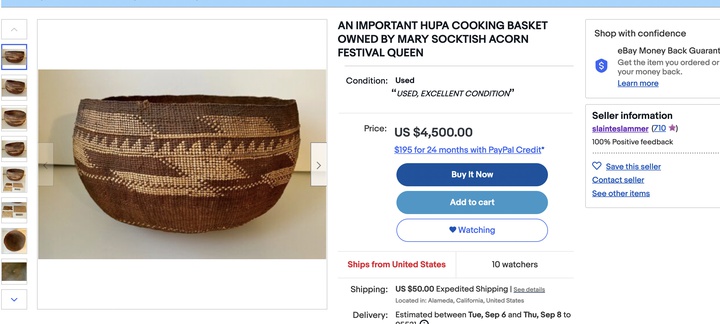

Alanna Lee Nulph says her "grandmother's grandmother" Mary Socktish wove this basket for the Acorn Festival, an event that hasn't been held for more than 100 years. | Screenshot from eBay

One item — a cooking basket belonging to Mary Socktish, Nulph’s great great grandmother — is being sold on eBay for $4,500. Socktish wove the basket for the Acorn Festival, which hasn’t been practiced in over a century, Nulph said. She said she reached out to the seller about three months ago.

“The seller used that knowledge we gave them about it as leverage against us to charge more for it,” Nulph told the Outpost. “Even though we offered him something like $2,500. We just wanted it back. It’s our family. It has not come home yet and the seller has created a barrier between us and it.”

When it comes to cultural items private individuals inherit, Nulph said she thinks people should reach out to the tribe they suspect those items to have originated from. The Yurok Tribe’s cultural department would gladly take possession of a basket or a piece of regalia that had been in private hands, Nulph said, but aren’t always able to purchase them.

Though there isn’t a law that says Native people have first rights to these items, Nulph said she didn’t think it would be too much of a stretch to have to present tribal ID to purchase them.

“I don’t know how it would work in practice, but that’s my feelings on it,” she said.

As for current effort to bring the basket caps back home, Garcia said he hopes to be able to work something out with the Encanto Gallery owner soon because the White Deerskin Dance ceremony is coming up.

“I extended an invitation to him, ‘Won’t you come to our ceremonies? You can see how we use the items and you can see how significant they are for us,’” he said. “He appreciated that. I think he even stated he would be willing to drive the items here back to us if we were to work something out. It would be good for everyone to come together in a good way and build that relationship and that rapport.”

Attempts to reach Clayburn and Matt Mais, the Yurok Tribe’s public information officer, were unsuccessful.

CLICK TO MANAGE