Jessica Cejnar Andrews / Tuesday, Oct. 18, 2022 @ 2:14 p.m.

Crescent City Pavement Plan Shows A Backlog of Needed Road Repairs That Would Cost Millions of Dollars

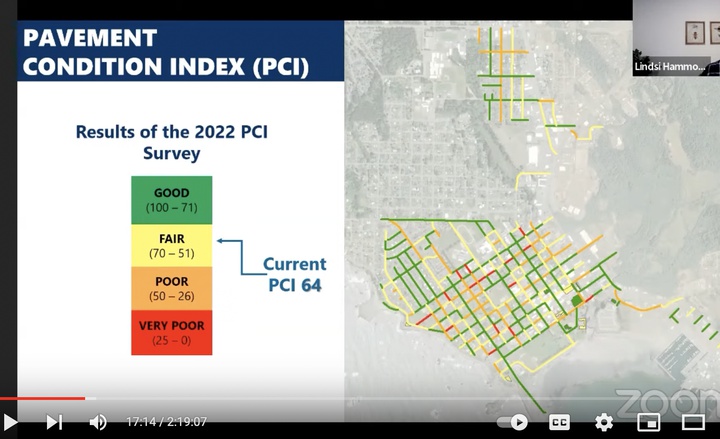

This map shows the condition of Crescent City's roads. | Courtesy of Crescent City

Crescent City’s mayor called an assessment of the city’s streets a good argument in favor of Measure S, the 1 percent sales tax that’s up for repeal on the Nov. 8 ballot.

But while public works staff has made a start at keeping good streets good, getting through a backlog of roads that need maintenance, reconstruction or rehabilitation will cost the city millions of dollars, said Lindsi Hammond, principal at GRI, a Portland-based engineering firm with an office in Brookings.

Though the Council wasn’t asked to make a decision after hearing Hammond’s pavement program and condition assessment presentation on Monday, City Manager Eric Wier said the Council has “big questions” to answer. He said the city will hold a workshop around the first of the year — after the election.

“Once we know the status of the Measure S revenues,” Wier said, “because obviously that’s going to play a huge role in how we can address the resources the Council has to make some of these decisions and then going forward.”

According to Hammond’s presentation, Crescent City’s network of streets have a weighed score of 64 on the pavement condition index (PCI). This means the condition of the city’s overall roads is in the fair category, according to this internationally accepted statistical measure, Hammond said.

About a third of Crescent City’s local and collector streets are in need of surface treatments such as crack seals or patching and possibly some better overlays, Hammond said. However, a quarter of the city’s network of streets is in poor to very poor condition and need new overlays or a full reconstruction, a more expensive endeavor than surface treatments, she said.

If the city maintained its current $250,000-a-year budget for street and pavement maintenance, its pavement condition index would drop to 59 after five years, according to Hammond. That would apply if the city only treated its collector roads, she said.

After five years, Crescent City would still have a backlog of roads that need pavement rehabilitation or reconstruction at a cost of nearly $41 million if it keeps within its current budget. It started out at $18.7 million, but Hammond said those costs increase over the years.

If the Crescent City Council increased the pavement budget to $1 million a year — about $5 million after five years — “we’re almost holding our condition steady,” Hammond said. The city’s PCI would drop from 64 to 63 and the backlog of roads needing rehabilitation would cost $36.49 million after five years, she said.

If Crescent City’s goal was to increase its PCI rating to 70, which is the high end of fair or the low end of satisfactory, the total cost would be about $7.25 million annually for a total of $36.77 million Hammond said.

Hammond’s final five-year scenario had Crescent City eliminating its backlog of roads needing rehabilitation or construction, which would cost $37.31 million. This, she said, is a “high water mark” and would boost Crescent City’s PCI rating to 92.

But if the city decided to make the repairs needed to increase its PCI to 70 over 20 years, that cost would be about $39.77 million.

“Both scenarios don’t have a backlog at the end,” Hammond said, adding that total funding also took inflation into account, though it can be variable over 20 years. “The other component, by stretching it out over a 20-year period network, the PCI declines by eight points. It’s still an 85, which is a fabulous PCI score, but just that delay of slowing the amount of preservation and rehabilitation (work) being applied causes a decrease in condition ratings.”

In her presentation, Hammond said a preservation-based approach is “where we keep good roads good at the lowest cost possible.” “Worst-first” is another approach that consists of reacting to a road in need of extensive rehabilitation. This, she said, isn’t sustainable and can get expensive.

She said the Council can use her company’s analysis as it pursues further rehab dollars, including future tax measures, and in deciding which streets should be addressed first.

According to Wier, Crescent City’s public works director, Jon Olson, already began a preservation project on three of the city’s main collector roads — 9th Street, Harding Avenue and portions of H Street.

Councilors in June approved a $412,000 contract with Hemmingsen Construction using Measure S dollars for that street maintenance and preservation project. About $500,000 in Measure S funding was allocated to that project, according to Wier at the Council’s June 22 meeting.

On Monday, Wier said another street that needs attention is A Street, which has portions that are OK and other stretches that are “really bad.”

“As we move forward, obviously Measure S funding is going to dictate a lot of what we can or cannot do,” he told the City Council.

At a candidates forum hosted by True North Organizing Network last week, Wier discussed the potential impact repealing Measure S would have on city services, including street preservation. Apart from Measure S dollars, which generated a total of nearly $2 million during the first year, Crescent City receives between $300,000 and $400,000 a year from the state’s gas tax, Wier said.

“We could complete a rehab of one block per year,” Wier said. “It would take us 400 years to get our streets in the shape they need to be.”

According to Wier, Measure T would undo Measure S in city limits, while Measure U would repeal Measure R in the unincorporated part of the Del Norte County.

A yes vote on Measure T eliminates the funding source the city has come to rely on, which fuels the police and fire departments and the Fred Endert Municipal Pool as well as pay for street repairs, Wier said.

On Monday, though he noted that having those Measure S tax dollars is crucial, Crescent City Councilor Blake Inscore said the city’s worst streets wouldn’t improve without additional funding.

“Even if we allocate a half million dollars annually, it’s just barely keeping us there,” he said. “We can continue to keep our good streets good and we can begin addressing some of the problems, but five years from now some of the worst streets will still be the worst streets.”

CLICK TO MANAGE