Jessica Cejnar Andrews / Tuesday, Jan. 30, 2024 @ 12:49 p.m. / Community, Elections, Local Government

Del Norte Judicial Candidates Opine on Mental Health, Criminal Recidivism, Juvenile Hall Closure, Challenges

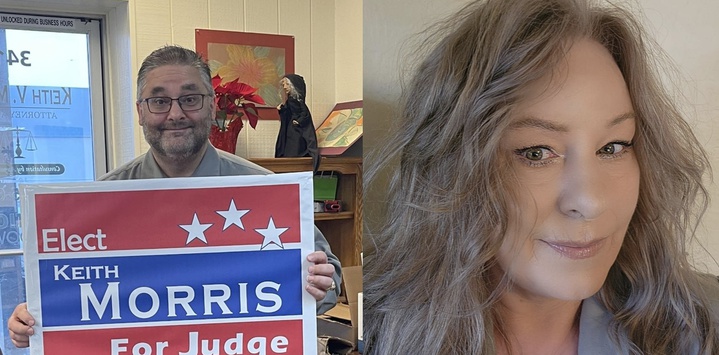

Del Norte County judicial candidates Keith Morris and Karen Olson

(Updated at 9:42 a.m. to correct an error.)

Though it wasn’t the testy-at-times debate Del Norte County supervisor candidates engaged in earlier in the evening, last week voters learned more about the attorneys hoping to become the county Superior Court judge.

Keith Morris and Karen Olson fielded questions at the Del Norte Association of Realtors’ candidate forum Friday. Though DNAOR board member Robin Hartwick noted that it’s not proper for judicial candidates to offer opinions about specific cases, she and her colleagues asked the candidates if they’re able to adequately punish offenders, whether they could be tough on crime and their thoughts on incarcerating those who are mentally ill.

Morris and Olson were also asked to opine on the recent closure of Del Norte County’s juvenile detention facility and how CARE Court would be implemented locally.

Both candidates are hoping to replace current Del Norte County Superior Court Judge Robert Cochran. Both have worked as public defenders in Del Norte County. Morris has also been a prosecutor, and has represented clients as a private attorney. He said he started his career in Del Norte County in 2003 as a deputy district attorney, working with Olson in Mike Reese’s office.

“I love the law, I love to practice law and I love to help people,” Morris said. “I’ve been fortunate enough to practice law in some 15 different counties in California.”

Those counties include Amador County, Placer County, San Joaquin, Tuolumne and in Yuba County. He came to Del Norte County in 2003, working in the DA’s office until 2008 when he went into private practice.

Morris said Olson convinced him to return to Del Norte County in 2017 due to a shortage of public defenders.

Olson said Morris was the first person she had in mind at the time.

An attorney practicing in Del Norte County for 23 years, Olson said she was a prosecutor and a defense attorney. She’s been a public defender, has dabbled in private law, working on civil rights violations, and has experience in family law and in juvenile dependency cases.

Olson said she felt becoming a Del Norte County Superior Court judge was a natural progression in her legal career, but added that Del Norte is her home.

“I have lived here for over five decades,” she said. “I have a vested interest in doing what’s best for this community. I want to make this community a safe place for my children and, hopefully at some point, for my grandchildren.”

During the Q&A period, Hartwick and her colleagues often put questions to a single candidate, though in the case of their query on CARE Court, both Olson and Morris were given a chance to weigh in.

California Governor Gavin Newsom’s signature mental health legislation from 2022, CARE Court — Community Assistance, Recovery and Empowerment Courts — rolled out in Glenn, Orange, Riverside, San Diego, San Francisco, Stanislaus and Tuolumne counties in October 2023.

Los Angeles County opened its CARE Court on Dec. 1, 2023. California’s remaining counties must implement CARE Court in December 2024.

CARE Court allows family, close friends, first responders and mental health providers to petition a court to compel a person with untreated mental illness into a court-ordered treatment plan, CalMatters reported on Oct. 10, 2023.

In June 2022, Del Norte County supervisors sent a letter to state senators Tom Umberg and Susan Talamantes Eggman, authors of the CARE Act, stating that the community lacked the resources to implement the law.

On Friday, when asked to explain CARE Court, both Olson and Morris acknowledged that Del Norte County doesn’t have the money or infrastructure to ensure it would be successful locally.

“CARE Court is a good idea. It’s a great concept,” Olson said. “But unfortunately, the state legislation is, in my opinion, passing off something to local communities that local communities cannot handle fiscally or manpower wise.”

Morris pointed out that when lawmakers enacted CARE Court, they didn’t attach money or infrastructure to it. Local communities are expected to implement CARE Court with their existing staff and attorney pool, Morris said.

Morris said he agreed with Olson that the rationale behind the CARE Court concept was good.

“The implementation of it just isn’t feasible right now,” he said. “This doesn’t make much sense.”

When answering a question about mental health incarceration “as a method for dealing with a lack of resources,” Morris said California hasn’t done enough to help communities deal with that population.

He pointed out that when a person’s competency to stand trial is in question, they should be sent to a state mental hospital until they are deemed competent. However, Morris said, a client who, on Jan. 26, was considered incompetent to stand trial wouldn’t get to that hospital until June or July. They would be sitting in the county jail, he said.

Morris said there are mental health courts, which he’s a believer in.

“If someone commits a crime and part of that crime is predicated on their mental health ‚ like they’re psychotic or they’re schizophrenic — and if the county Behavioral Health Department believes you’re qualified, then you’re diverted away from the criminal courts and you go to treatment and therapy, take your medication, and you’re monitored by the court with periodic reports,” Morris said. “[If] you’ve successfully completed your mental health case plan, the case is dismissed. The idea being we’ve diverged from incarceration, gave you health and you won’t come back.”

As for those who are struggling with drug addiction as well as mental health issues would be for them to commit to addiction treatment, Morris said.

When asked if she considers herself tough on crime, Olson said judicial candidates have to be careful not to take positions on political or religious issues. Judges can’t be seen to be biased or partial in future cases — everyone deserves the right to a fair trial, she said.

Olson assured voters that anyone coming into her courtroom would get a fair and impartial judge and would receive a sentence based on the facts of their case.

“I would not want to see any judge punish a crime,” she said. “I think it’s a better thing to punish the person for committing the crime because there’s many different reasons that people commit crimes. I think a good judge will look at that and take that into account.”

As for the closure of Del Norte County’s juvenile hall, Olson said it’s too soon to understand what the ramifications will be.

The Del Norte County Board of Supervisors officially eliminated its juvenile hall division in September, transitioning the unoccupied facility to a Youth Opportunity Center. Detained juvenile offenders are being housed in Humboldt and Shasta counties primarily.

On Friday, Olson noted that she and Morris don’t see many juvenile delinquency cases — they primarily handle serious violent felonies. But, she said, she thinks closing the local detention facility would have a significant effect on this community.

“Especially with the families that do have kids in the delinquency system because now they have to be shipped out,” Olson said. “I think that was a burden upon the people that are here in Del Norte County with kids in the system. They’re on a limited income and they are trying to figure out a way to see their kids. I think that family support is what’s going to help these kids get out of the system and become more productive, law-abiding children.”

When asked what the leading factor is in unpunished criminal activity, Morris noted that as public defenders the “frequent flyers” both he and Olson see are often struggling with alcohol and drug addiction.

“If you cure the addiction, you cure the behavior,” he said.

Others are struggling with mental illness, Morris said.

“The percentage of people in society who are just criminals is probably pretty small when you get down to it,” he said. “We see doctors, lawyers, teachers, pastors, and other professionals who brush up against the criminal justice system and they need help. They’re not criminals who need to go to state prison. They need help and they need to navigate the court system [if] they want to get on with their lives.”

Olson said Del Norte County’s judiciary is struggling with a lack of resources and a lack of funds. Those are needed to expand the courthouse to include a third courtroom and a third judge, she said.

“I think this is a common cry in, not only the legal system, but law enforcement as well,” Olson said. “We just don’t have the numbers to do and provide the services that our community really needs.”

Ballots in California’s March 5 primary election will be sent to Del Norte County voters starting Feb. 5. To read coverage of the Del Norte County Districts 2 and 5 supervisor forum, click here.

CLICK TO MANAGE