Jessica Cejnar Andrews / Wednesday, April 26, 2023 @ 4:12 p.m. / Environment

Smith River CSD General Manager Says Drinking Water's Safe; Abandoned Mines Still Need Remediation, Supervisor Howard Says

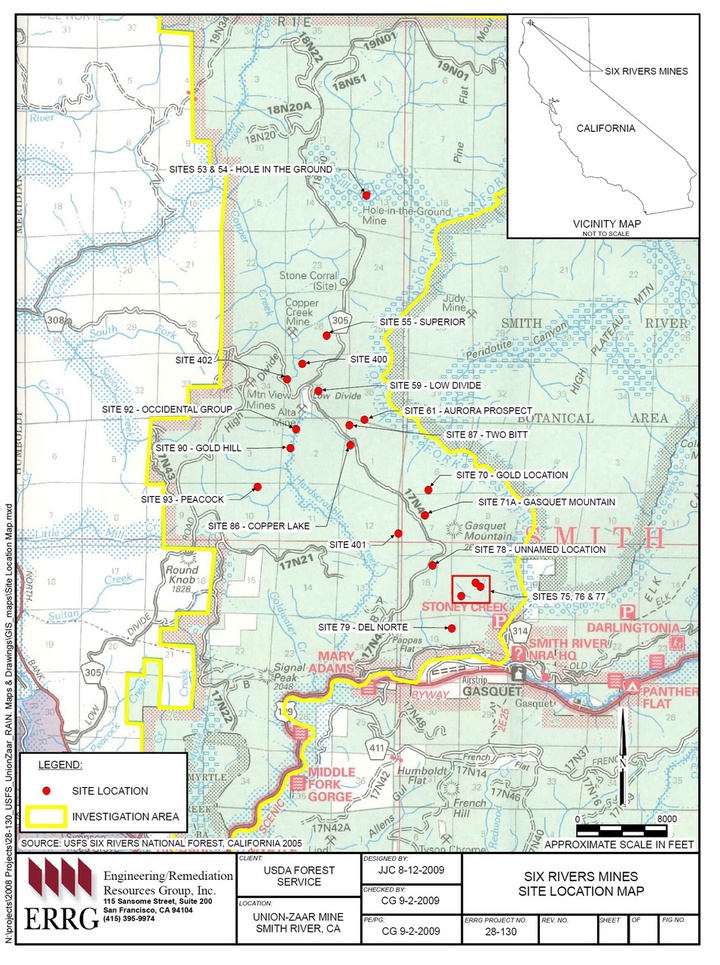

This map from a 2007 report prepared for the U.S. Forest Service shows the location of the Union Zaar Mine and other abandoned mines in the Smith River National Recreation Area.

Previously:

###

In its three-decade history of testing for the substance, arsenic has shown up once in Smith River Community Service District water — well below state and federal maximum contamination limits, according to General Manager Jeff Beard.

Beard spoke to Del Norte County supervisors Tuesday about a month after Smith River Collaborative Co-Chair Grant Werschkull told them that more than 90 abandoned mines were leaching heavy metals, including arsenic, near the headwaters of Rowdy Creek.

Werschkull, who was seeking a letter of support for the U.S. Forest Service to obtain Superfund grant dollars to remediate those mines, linked that issue with Smith River’s drinking water. Beard said no one contacted the Smith River CSD prior to the March 28 meeting.

“If anybody would have come in and asked for our test results, I feel the community wouldn’t have been as concerned or worried about (their drinking water),” Beard said. “I wasted a lot of time on phone calls and chasing down data. I brought a sample down to Eureka to get tested. There was a lot of foot work that had to take place over the last month that could have been easily avoided if somebody just reached out to us.”

Werschkull declined to comment following Tuesday’s meeting.

The Smith River CSD gets its water from four wells that sit alongside Rowdy Creek. They’re drilled about 40 feet into the ground, roughly 20 feet below the water surface level at the creek, Beard said.

The Smith River CSD has tested its water for arsenic about nine times in the past 30 years, Beard said. The one time it showed up, in 2019, arsenic levels were 2.9 parts per billion. The maximum contamination limit the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the California Water Resources Control Board sets is 10 parts per billion, Beard said.

“That’s the highest it’s ever been and the only time it’s actually ever shown up in our system,” he told supervisors. “There were a few other contaminants brought up at the meeting on March 28, one of them being copper and the other being chromium. Chromium has always been non-detect throughout the entire history of the district.”

Copper is typically tested for at the taps belonging to the water district’s customers, Beard said. There are also “a ton of different variables” associated with that testing, so the Smith River CSD relies on its customers to conduct those tests, he said.

District 3 Supervisor Chris Howard, whose district includes the Smith River National Recreation Area and the community of Smith River, said he could understand why the way Werschkull framed the issue in March upset residents. But Howard said he still hopes the Board of Supervisors can help support remediating those mines.

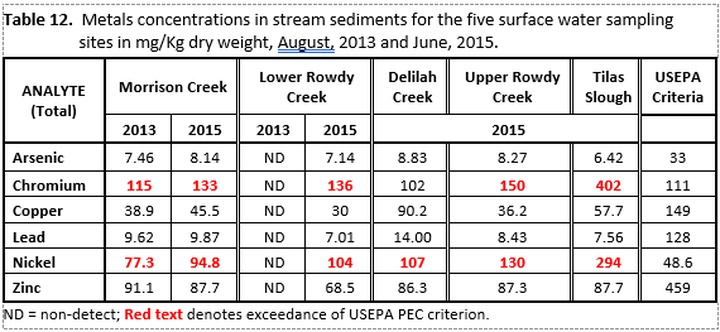

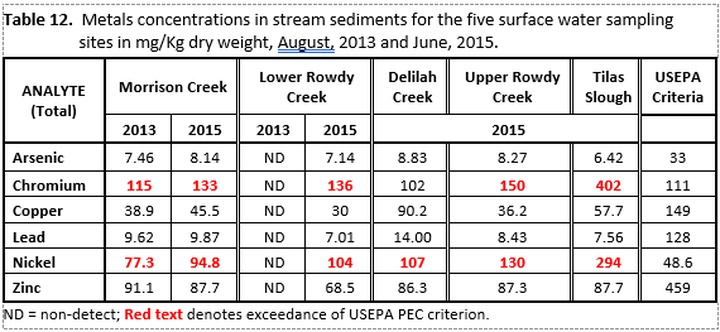

Howard said he also regretted Werschkull specifically mentioning arsenic when there are unsafe levels of chromium and nickel, according to data he obtained from Rich Fadness, regional coordinator for the state’s Surface Water Ambient Monitoring Program.

That data, taken between 2008 and 2015, showed elevated levels of chromium and nickel in Morrison Creek, Lower and Upper Rowdy Creek, Delilah Creek and Tillas Slough as well as in the Smith River at Sarina Road. Arsenic levels were below what the U.S. EPA deems unsafe, according to that data.

Water Quality Control Board data showing heavy metal levels in creeks in the Smith River area. | Courtesy the California Water Quality Control Board

In an April 10 email exchange with Howard, Ben Zabinsky, water resources control engineer with the state Water Quality Control Board, said the data concerns concentrations of metals in sediment and “cannot be directly compared to water column drinking water standards.”

According to Howard, those creeks and the Smith River at Sarina Road flows through land owned by his employer, Alexandre Dairy.

“What I was referring to was nickel and chromium concentrations — which is what those cleanups are trying to abate — are relatively high,” Howard told the Outpost on Wednesday. “It obviously makes sense given the geology of the region and what they were mining for there, which (were) these two components.”

Water Quality Control Board data showing heavy metal levels in creeks in the Smith River area. | Courtesy the California Water Quality Control Board

According to Howard, the U.S. Forest Service identified three abandoned mines near the Rowdy Creek headwaters in 2009 that it wanted to remediate. One of those mines, the Union Zaar Mine, is an old copper mine along the banks of Copper Creek, which is a tributary of Rowdy Creek.

According to the executive summary of a 2007 report prepared for the Six Rivers National Forest by Engineering Remediation Resources Group Inc., people who come in contact with the mine waste piles at the Union Zaar Mine site could be exposed to unsafe arsenic levels. Sediment in Copper Creek could also pose an unacceptable risk to spawning fish and amphipods around the Union Zaar Mine, according to that 2007 report.

In a statement to the Wild Rivers Outpost on Wednesday, a Six Rivers National Forest spokesperson said it’s always searching for federal funding to monitor abandoned mines within the Smith River National Recreation Area.

“Part of the USFS mission is to protect watersheds by assessing and remediating legacy mine sites on Forest Service public lands. The USFS is continuing to remediate these sites and developing a plan to address any potential hazards on (Forest Service) lands,” she said. “The United States Forest Service manages and protects millions of watershed acres across the nation that supply water for communities and municipalities, but it is not within the jurisdiction or authority of the USFS to determine the quality of water downstream at the point of use.”

In March, Werschkull told county supervisors that remediating these 90 mines could consist of pulling the material back from the creek so it wouldn’t leach into the water. He said it would cost about $2.5 million. The Smith River Collaborative had hoped to harness multi-party support to obtain nationally competitive Superfund dollars to spearhead those efforts.

On Tuesday, Howard said he still hoped his colleagues on the Board of Supervisors could support these remediation efforts.

“As I said in that Board meeting, I thought it would have been a no-brainer,” he said. “It’s too bad it was framed the way it was, but now [that] we’ve got some attention on the issue maybe it’ll help Congressman Huffman to seek the necessary funding to treat (those mines).”

CLICK TO MANAGE