Jessica Cejnar / Friday, Sept. 10, 2021 @ 4:39 p.m. / Community, Obits, Our Culture

Raymond Mattz, Whose U.S. Supreme Court Win Reaffirmed Yurok Rights to the Klamath River, Dies At 79

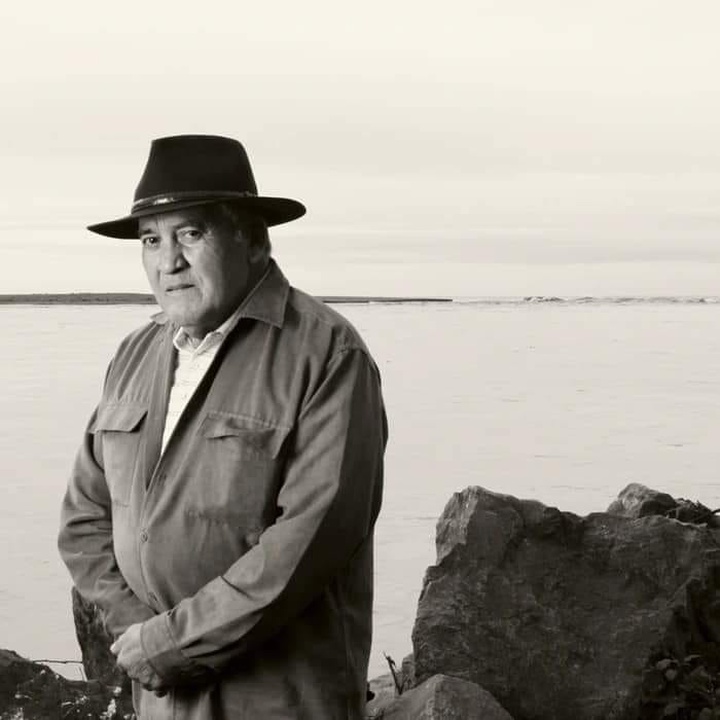

Raymond Mattz's fight for Yurok fishing rights led to the landmark 1973 U.S. Supreme Court case, Mattz v. Arnett. Photo courtesy of the Mattz family.

Raymond Mattz, whose fight for his people’s right to fish on the Klamath River included multiple arrests, clashes with federal agents and a legal battle that led to a landmark U.S. Supreme Court Case decision that reaffirmed the Yurok Reservation as Indian Country, died Sept. 2. He was 79.

Mattz had been dealing with breathing and heart problems, including a heart attack, for about two years, according to his niece Susan Masten. Finally, she said, he stopped breathing and his heart gave out. Despite his poor health, Mattz continued to serve on the Yurok Tribe’s cultural committee and advocate for the river and its salmon runs.

“Fishing was his whole world and so being on the river is what he did with his children and his grandchildren,” Masten told the Wild Rivers Outpost. “And then our ceremonies, our Brush Dances, that’s what he did with his children and grandchildren.”

Mattz, who grew up at Brook’s Riffle and Requa, came from a long history of warriors who fought for Yurok rights, his grandniece, Amy Cordalis, said. His ancestors four or five generations ago signed a treaty with the federal government that, though it was never ratified, established the Yurok Reservation by executive order in 1855, she said.

However, following the federal General Allotment Act in 1888, the California government in 1892 opened the Yurok Reservation to settlement from non-natives, according to Cordalis. As a result, any native living there had to obtain a state permit to fish and could only catch two salmon per year, she said.

“That was a huge affront to our way of life,” she told the Outpost. “The family and Ray and his mom, Geneva Mattz, and his dad, Emery Mattz, they knew that was wrong. The state would prosecute Yurok people just for fishing on the river. Uncle Ray got arrested over and over for just fishing on the river. But every time he said, ‘This is my right.’”

In 1969, Mattz was fishing at Brooks Riffle when a California game warden confiscated his gill nets and gave him a citation, according to Cordalis. Mattz went to state court and demanded his nets back, telling the judge “these are my Indian rights, you can’t keep me from fishing,” she said.

According to Cordalis, the judge told Mattz to pay him $1, said he’d return his nets and would drop the charges. That wasn’t good enough, she said.

“Uncle Ray said, ‘No. I am pushing this legal issue through the courts because this is my right,’” Cordalis said. “He pushed the case. And the issue of whether the Yurok Reservation was still Indian Country such that Indian people, Yuroks, still had the right to fish under federal law and under aboriginal rights — their Indian rights — went all the way to the Supreme Court.”

In the 1973 U.S. Supreme Court case, Mattz v. Arnett, the state argued that the General Allotment Act terminated the Yurok Reservation, it didn’t retain its Indian character and gave the state jurisdiction over the lower Klamath River.

The Supreme Court disagreed, Cordalis said.

“The Supreme Court looked at all the information in front of it and said, ‘No, this land, the Yurok Reservation, is still Indian country because the Indians never left, the Indians kept fishing and the land has retained its Indian character,’” Cordalis said. “Because of that Yurok people had federally-reserved fishing rights on the river on the reservation.”

Mattz v. Arnett laid the foundation for the Yurok Tribe to eventually express its sovereignty, Cordalis said. It empowers the tribe to offer government services in the Klamath area and to advocate for clean water, for a healthy river and healthy fish, she said.

But it didn’t come without a personal cost to Mattz, Cordalis said. He was an enemy of the state from the 1960s through the 1980s, she said, comparing him to American Indian Movement leader Billy Frank and to Civil Rights leaders Martin Luther King Jr. and John Lewis.

Up until that Supreme Court decision, most Yurok people fished at night, Masten said. Following Mattz v. Arnett, Yurok fishermen were met with hostility from non-native fishermen, she said.

“They felt we shouldn’t be there,” Masten told the Outpost. “They started saying we were taking all the fish because they didn’t want us to be there. They were used to having the river for themselves and so then they started to lobby against us fishing.”

Following Mattz v. Arnett, the state turned jurisdiction of the river over to the federal government, which put a moratorium on fishing, Cordalis said. When Yuroks continued to fish, federal agents, decked in riot gear, were sent to enforce the ban, leading to the 1978 Klamath Salmon Wars.

At the time, native people across the country were taking part in the American Indian Movement, Cordalis pointed out.

Federal marshals raided Mattz’s home looking for fish, Cordalis said. He was beaten repeatedly. The federal government viewed Mattz as the leader, she said, and targeted him. Though he went through violence and trauma in the federal government’s attempt to terminate Indian fishing, he won, Cordalis said.

“He won for all of us — it feels so powerful to say it in those words,” she said. “It’s hard for family members, tribal members and community members to understand what he did and his role in that whole history.”

Following the Salmon Wars, tribal fishermen formed the Yurok Fishers Association and selected Masten as the chair. They met on a regular basis and “carried the word forward” to the Klamath Fisheries Management Council, the Pacific Fisheries Management Council, the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the state and federal governments.

Masten said her uncle told her what to say and often went to meetings with her.

Mattz served as a Yurok Tribal Councilman, was a member of the Yurok Cultural Committee and the Natural Resources Committee working on fisheries and forestry issues, Masten said.

Mattz, who had a fishery at Omagar Creek near Brooks Riffle, continued to advocate for the river, including dam removal and salmon habitat restoration.

“He really wanted it to be healthy again,” Masten said. “He really wanted for the natural populations to be built back up and for the dams to come out and for the rivers to be healthy again and the ecosystem to be healthy like it was before.”

Cordalis, who was the Yurok Tribe’s general counsel and now represents the tribe on dam removal and Klamath River restoration, said she’s grateful that she can continue his advocacy.

“As the next generation I can step into this work and others can step into this work and it’s safe,” she said. “I’m not the subject of a federal termination plan. We go to war in the courtrooms, but it’s safer.”

The Mattz family will send Raymond Mattz on his final boat ride at 10 a.m. Saturday in Klamath. Grave-side services will be held at 1 p.m. at Howonquet Cemetery in Smith River.

CLICK TO MANAGE