Jessica Cejnar Andrews / Wednesday, July 17, 2024 @ 10:21 a.m.

Renewable Energy Advocate, Former Coos County Elected Official Urge Curry Commissioners To Re-think Stance On Offshore Wind Energy

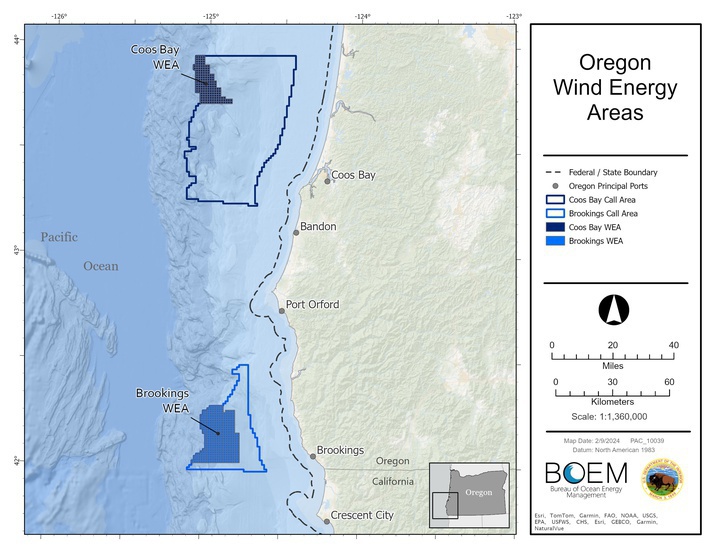

The U.S. Bureau of Ocean Energy Management is expected to hold lease auctions for two areas off the Southern Oregon Coast to renewable energy developers in October. | Map courtesy of BOEM

Previously:

• Curry County On Offshore Wind Energy: 'No Way In Hell'

###

A former Coos Bay elected official and the executive director of Renewable Northwest are pushing back against statements made at a Curry County Board of Commissioners meeting on July 3 regarding offshore wind energy development.

While the U.S. Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, or BOEM, may hold a lease auction in October, it will take years of analyses and studies before renewable energy companies determine if it’s feasible to establish floating wind farms off the Southern Oregon Coast, both Melissa Cribbins and Nicole Hughes say.

They’re also urging Curry County commissioners to ask questions about the potential benefits — as well as the impacts — their communities could see from offshore wind instead of threatening to sue BOEM.

“This is a very under-resourced county already,” said Hughes, Renewable Northwest’s executive director. “There could be lots of good opportunities. We’re talking about 30 to 40 years of economic investment that people who haven’t been born in the county yet could receive. If I were a county commissioner and I was thinking about opportunities for my county, I would want to find the people who have information and ask questions.”

Four years after BOEM began exploring the potential for wind energy generation off the Oregon coast, the federal agency is expected to hold a lease auction for two areas to developers. These two areas total 194,995 acres off of Coos Bay and Brookings.

According to a news release from the Department of the Interior on April 30, the two areas have the potential to power more than a million homes.

Since March 2020, BOEM has worked with the state Department of Land Conservation and Development to determine whether offshore wind is feasible for Oregon. The process has included multiple rounds of stakeholder meetings, including with members of the public.

In a conversation with the Wild Rivers Outpost on July 11, Hughes said Renewable Northwest began engaging in the offshore wind energy conversation about two years ago.

The nonprofit organization has advocated for clean energy policies for about 30 years focusing on Oregon, Washington, Montana and Idaho — the footprint of the Bonneville Power Administration.

Hughes said Renewable Northwest became engaged in the offshore wind energy discussion when its representatives began noticing misinformation circulating in the community about the topic. It sought to alleviate that misinformation by creating a coalition of people wanting to know more about the topic, which included fishermen and local port commissions

“Our goal is not to come into a community and say, 'This is how you should be thinking about this,' but to say, ‘We’re here to provide some information if you want it,’” Hughes said. “We thought it was important for the state to develop a roadmap on what offshore wind might look like.”

Developing that roadmap is a cornerstone of Oregon House Bill 4080, which Gov. Tina Kotek signed into law on March 27. It also calls on the Department of Land Conservation and Development to conduct a federal consistency review on BOEM’s offshore wind energy process, Hughes said.

Shortly before Kotek signed HB 4080 into law, the Curry County Board of Commissioners approved a resolution calling on BOEM to coordinate with local governments on actions that may affect their recreational areas. That resolution invoked the Coordination Development Act of 1963 and was added to the March 21 agenda last minute by Commissioner Jay Trost.

Trost referred to that resolution on July 3 when he and his colleagues Brad Alcorn and John Herzog discussed putting an advisory question on the November ballot to gauge the community’s feeling about offshore wind energy development in the area.

Trost said asking voters to weigh in on offshore wind energy could be used as ammunition for potential legal action. He said a BOEM representative had acknowledged receipt of the March 21 resolution and asked if the Board of Commissioners wanted to discuss it further.

The BOEM representative didn’t respond when Trost told him he and his colleagues would like to discuss the resolution further, the commissioner said.

“I think what I’d like to bring to the attention of this group is should [BOEM] not respond within the parameters in which we’ve requested, I think we need to consider possible legal action,” Trost told his colleagues.

At that meeting, commissioner-elect Patrick Hollinger, who ran against Herzog earlier this year, mentioned Renewable Energy — though he called it ReNew Global, or RNW.

Hollinger said Cribbins had contacted him on behalf of Renewable Energy to invite him on a trip to Scotland to visit “windmill factories” there.

Last week, Hughes told the Outpost that her organization is facilitating a trip to Scotland for delegates representing the fishing sector, local tribes and government agencies, though Hollinger wasn’t invited.

These types of trips are common, Hughes said. The one Renewable Northwest is planning coincides with the development of Oregon's offshore wind roadmap.

The process for developing the offshore wind roadmap kicks off in September and will be done by fall 2025, Hughes said.

“If you look at the timeline for BOEM and then you look at the timeline for the road map, people are concerned about moving forward with a lease auction prior to the road map being completed,” she said. “That was unfortunate timing. [But] we still think the roadmap can have significant influence over this process.”

Though Curry County residents may feel that the train has left the station on offshore wind, Hughes said from her organization’s perspective, it’s barely time to start packing to get on the train.

Once BOEM holds its lease auction in October, renewable energy companies have the opportunity to determine if a project is feasible, Hughes said. This process will include financial analyses, geological studies and meetings with people in the community, she said.

If a company decides they can build an offshore wind energy project off the coast, it will go back to BOEM, which triggers another round of environmental impact studies, mitigation requirements and other review measures, Hughes said.

“We’re looking at a 10 year process,” she said.

Cribbins, who served on the Coos County Board of Commissioners from 2013 and 2022, was an alternate representative for the county on BOEM’s Oregon Intergovernmental Renewable Energy Task Force — the same task force that now includes Trost as Curry County’s representative.

There’s also a federal consistency review process through the state Department of Land Conservation and Development’s Oregon Coastal Management Program. The department takes public comment and hears from other agencies to figure out the impacts federal activity may have on state coastal resources.

BOEM is currently going through a first federal consistency review process, Cribbins said. Another one will be necessary when BOEM releases a construction permit, she said.

Cribbins was a county commissioner during the Jordan Cove Energy Project controversy. The project, spearheaded by Calgary-based Pembina, called for a 229-mile-long natural gas pipeline that would have run from Malin, Ore., crossed five major rivers including the Klamath and the Rogue, to a terminal in Coos Bay.

In 2021, facing opposition from tribes, fishermen and other Southern Oregon residents, Pembina permanently canceled the project.

According to Cribbins, the Jordan Cove project went through federal consistency review. The federal agency in that case was the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, or FERC. At the end of that process the Department of Land Conservation and Development Commission found the project wasn’t consistent with state law and “there’s no way to make it that way,” Cribbins told the Outpost.

“There were a lot of concerns about air quality emissions,” she said. “If you look at point source pollution, [Jordan Cove] would have been one of the largest point source emissions in the State of Oregon.”

With offshore wind energy development in Southern Oregon, however, Cribbins noted that the Department of Land Conservation and Development have held four public meetings so far, which they didn’t do for Jordan Cove.

She said the department will hold future meetings as the BOEM and the offshore wind energy process moves ahead.

As a former county commissioner, Cribbins said she understands where her counterparts in Curry County are coming from.

“Whenever you have big change potentially coming to the community and people are feeling like they’re not getting the information they need, the response is to want it to go away,” she said. “Politically, I completely understand where they’re coming from. I do think this is an opportunity for the area.”

Cribbins said she thinks there is value in local elected and tribal officials and representatives from the fishing sector taking a trip to New Bedford, Mass., and Scotland to see how offshore wind energy is impacting communities there.

It’s an opportunity for representatives in Oregon to talk to leaders in those communities about the impacts, the lessons they have learned and what they wish they had known before the process began, Cribbins said.

She said she’s not sure how helpful Curry County’s potential advisory question on a November ballot regarding offshore wind energy will be.

“I don’t know that it actually elevates your concerns above that of another similarly situated stakeholder,” she said.

Hughes said there is still a lot of opportunity for Curry County residents, as well as county commissioners, to provide feedback and guidance on offshore wind energy development in their community.

“The individuals who are saying 'We don’t want this' and 'We’re going to file a lawsuit,' really what they’re saying is 'We’re not open to talking about it and so we’re not going to be engaged,'” she said, adding that she’s confused as to what Curry County would sue for.

“At the end of the day, the county doesn’t have the authority to say 'yes' or 'no' to one of these projects. They’re sending the signal that they’re not open to conversation.”

CLICK TO MANAGE