Jessica Cejnar Andrews / Friday, Feb. 16, 2024 @ 2:58 p.m. / Community, Homelessness, Oregon

St. Timothy's, Brookings Get Their Day In Court; Both Sides, Plus U.S. DOJ, Present Oral Arguments

Parishioners and clergy members supporting St. Timothy Episcopal Church line up outside the James A. Redden Federal Courthouse ahead of opening arguments in the church's lawsuit against Brookings. | Jessica C. Andrews

U.S. Magistrate Mark D. Clarke promised supporters of St. Timothy Episcopal Church and the attorney appearing for the City of Brookings that he wouldn’t make them wait long for his decision.

“I don’t think anybody in the courtroom would disagree with the notion that you folks are doing good things,” Clarke told church officials and parishioners. “The city doesn’t dispute that. We’ll go back and look at the briefing and look at the record. You’re all doing good things for your community for sure regardless of how this all works out.”

Both sides — along with Max Lapertosa, trial attorney for the U.S. Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division — presented oral arguments in a Medford federal courthouse on Thursday.

At issue is whether a City of Brookings ordinance requiring a conditional use permit and restricting when organizations can feed the hungry imposes an undue burden on St. Timothy’s religious beliefs.

In an email to parishioners on Friday, ordained deacon Cora Rose, an attorney who operates St. Timothy’s legal aid clinic, said both parties have a motion for summary judgment before the court, which allows the judge to rule without a trial. The judge could also grant the City of Brookings’ motion to dismiss the church’s claims, she said.

“The judge may also grant either or both parties’ motion for summary judgment partially,” Rose said. “That certain (sic) claims or defenses are established and will not need to be proven at a trial.”

If the judge denies all three motions — the city’s motion to dismiss and either party’s motion for summary judgment — the case will move toward a trial, Rose said.

On Thursday, an attorney for the city, Heather Van Meter, of Miller Nash LLP, told the judge that Brookings officials had tried to engage with St. Timothy’s before adopting its ordinance in October 2021.

This included holding a workshop for those who provide “benevolent meal services,” she said.

According to Van Meter, then-mayor Ron Hedenskog, who had managed St. Timothy’s kitchen ministry for 10 years, was adamant that the church be allowed to continue providing meals.

“Hedenskog strongly [believed] that the benevolent meal services needed to continue in the face of significant public pressure to end meal services at all. Everywhere,” Van Meter said, adding that the ordinance was being drafted in the middle of the Delta wave during the COVID-19 pandemic. “People were upset with the city. Mayor Hedenskog’s response was we need to create a conditional use permit — some kind of process — so these meals can continue.”

St. Timothy’s serves between 35 and 68 meals three to four times per week for a total of between 105 and 272 meals, according to the city’s motion for a summary judgment filed Oct. 6, 2023.

On Thursday, before arguments got underway, Clarke asked the church’s attorney, Samantha Sondag, of Stoel Rives LLP, to keep her arguments to claims that the city violated the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act.

Clarke said he read both the plaintiff’s and city’s motions for a summary judgment as well as the statement of interest from the U.S. Department of Justice and a brief from the Notre Dame Religious Liberty Clinic. And after 16 years on the federal bench, he said he was well briefed on the Constitutional aspects of the case.

Clarke asked Sondag to focus her arguments on RLUIPA since the statute was new to him and he was working to get up to date on it.

Under the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act, zoning and landmark laws that substantially burden the religious exercise of churches “absent the least restrictive means of furthering a compelling government interest” are prohibited.

This prohibition applies when the state or local government entity imposing the substantial burden receives federal funding, whether it affects interstate commerce or if the burden arises from the local government’s procedures for making “individualized assessments” of a property’s uses.

Sondag argued that the city’s determination in July 2021 that St. Timothy and other entities were feeding the hungry in residential zones -- as well as the original ordinance the Council adopted in 2021 laying out restrictions for those meal services, and an April 2023 abatement notice delivered to the church -- constituted individualized assessments that imposed a substantial burden.

The city’s April 2023 abatement notice, Sondag noted, targeted all social services St. Timothy’s offers, in addition to its providing meals in a residential zone without a conditional use permit.

The Brookings City Council’s November 2023 decision to amend its benevolent meal service ordinance “in response to one unpermitted benevolent meal provider” is another example of an individualized assessment imposing a substantial burden on St. Timothy’s, Sondag said.

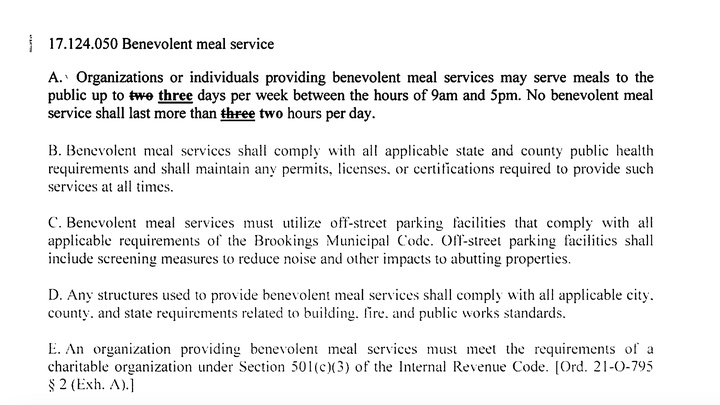

Brookings' benevolent meal service ordinance as amended on Nov. 13, 2023.

The church had been holding free lunchtime meal services since 2009. Other local churches also offered meals on other days of the week at about this time. However at the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, when most churches stopped offering meals, St. Timothy’s increased its ministry to fill in the gap, Sondag said.

St. Timothy’s also offered a space for overnight camping in response to a temporary Brookings City Council decision in 2020 in response to then-Gov. Kate Brown’s “stay home stay safe” order.

When that proved disruptive, the church enrolled in the Brookings Police Department’s Property Watch Program, which allows officers to order “non-approved individuals” to leave the property. St. Timothy’s stopped allowing overnight camping at the church in response to continued disruptions that included assaults and a hospitalization of an individual struggling with mental illness.

The church continued to participate in the Property Watch Program, however, Sondag told Clarke.

The church’s attorney argued that the City of Brookings crafted its benevolent meal service ordinance to deliberately place conditions on St. Timothy’s. She cited emails between city officials in 2020 before they received a petition from residents in 2021 asking how Brookings could use provisions under the Oregon Health Authority’s definition of a restaurant to place conditions on the church.

In June 2021, St. Timothy’s applied for and received a restaurant/commercial kitchen license through OHA. Sondag also cited communications between the city attorney and the Curry County Public Health Services in 2020 asking it to review the activities of certain city establishments.

“That is where counsel for the city says the city appreciates the positive benefits the meal service provides the community,” Sondag told Clarke. “[But] it is concerned about possible unintended health impacts. Those communications started only a couple of months after the emails internally discussing the possibility of reclassifying St. Timothy as a restaurant. And then the petition comes.”

Led by a resident living near the church’s Fir Street property, 29 people signed a petition “to remove homeless from St. Timothy church.” It was presented at an April 12, 2021 City Council meeting.

Finally, Sondag spoke to U.S. Supreme Court and 9th Circuit Court of Appeals precedent about the government’s responsibility to demonstrate that any laws or ordinances applying to churches and religious institutions were the least restrictive means.

“There is not anything in the evidence in the records that anything besides [Brookings’] ordinance was considered,” she told Clarke.

In this 2023 file photo, Jay Lindsay receives a meal from Smith River United Methodist Church volunteers at St. Timothy Episcopal Church. | Jessica C. Andrews

In response to this point, Clarke asked what would happen if Brookings had asked St. Timothy’s if it would agree to a more limited set of restrictions. He echoed a statement made in testimony from St. Timothy’s pastor, Father Bernie Lindley, and Diana Akiyama, bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Oregon.

“Could the city do any limited focused restrictions that St. Timothy’s would say, ‘That’s fine. We get the seven days a week that we can do our ministry, but we understand we shouldn’t do it in the middle of the night,’” Clarke said. “Or would any restrictions be a restriction on your ‘feeding the hungry when they’re hungry?’”

Sondag cited St. Timothy’s applying for a restaurant license and a permit to offer overnight camping space in response to the City Council’s 2020 COVID-19 ruling as evidence that they agree there should be restrictions on the church. The church also agrees that they shouldn’t be “hosting a party in the middle of the night,” Sondag said.

“I hesitated to respond to that because of the language of the ordinance,” she said. “And this is where the vagueness [comes in]. If someone that Father Bernie doesn’t know, if someone is displaced from a fire and comes to the church door and is 9 p.m. and Father Bernie is there… he will let that member of the public in and give them a meal.”

Sondag also referred to Brookings’ abatement notice against all social services the church.

“There is real concern that this type of ordinance couldn’t be manipulated in a way that prevents that sort of religious action,” she said.

Van Meter said the concern about benevolent meal services arose due to significant public pressure for the city to do something about public safety, crime and health and welfare issues at the church and at nearby Azalea Park. These concerns arose in the middle of the pandemic, she said, when there were substantial restrictions on personal movement and state public health orders were changing on a weekly basis.

“There were long lines of people who were not six feet apart, not wearing masks at St. Timothy’s,” Van Meter said. “At least some of those concerns arose in that context, which is in part of the emails to OHA in 2021.”

The petition Sondag referred to came from a place of general public welfare concern, Van Meter said. When city staff began looking into those issues, she said, that’s when Hedenskog and then-city manager Janell Howard realized that based on the number of meals St. Timothy’s was providing, it constituted a restaurant.

“Not because the city says so,” Van Meter said, “but because the state statutes and the Oregon Health Authority say so.”

Van Meter said all of the witnesses, including Hedenskog, Howard and Hedenskog’s former colleague on the City Council, Ed Schreiber, were questioned about their Christian beliefs. They’re all church-going individuals, Van Meter said.

The current Brookings City Council voted to terminate Howard as city manager in January after she pleaded no contest to a theft violation in December 2022 after being caught shoplifting from Fred Meyer in July 2022.

Hedenskog and Schreiber, along with their former colleague Michelle Morosky, were recalled in November 2023, nearly a year after they voted to reinstate Howard as city manager despite the theft violation.

On Thursday, in response to Clarke, who asked if the city was trying to dispute that serving the needy is at the heart of the Christian faith, Van Meter said St. Timothy’s serving meals at its church wasn’t allowed in the city’s land-use code and Hedenskog demanded city staff figure out a way for the ministry to continue.

Clarke then asked what the city’s ordinance restricting meal services was trying to do.

According to Van Meter, when creating the ordinance, the city invited all benevolent meal providers to a June 2021 workshop. She noted that they all happen to be churches. The city had asked them “what do you guys need so that you can continue doing what you’re doing?”

St. Timothy’s at this point had gone on record saying they were going to sue the city, Van Meter said. The church didn’t take part in that workshop, she said.

“What the other groups who were providing benevolent meal services said was, ‘well, we think, you know, one day a week was probably fine for them,’” Van Meter said. “The city exceeded the number of days, the number of hours.”

According to Van Meter, though churches attending that workshop thought feeding the needy one or two hours was enough, the city allowed them three hours. Churches also indicated that offering meals once per week was enough and the city allowed them, initially, two days per week and, after the ordinance was amended in November, three days per week.

Clarke asked Van Meter how those restrictions aren’t considered substantial interference with a church’s faith-based activities.

“If their faith is grounded on ‘we feed the hungry when they’re hungry, we don’t feed them because the government says we do it on Tuesday morning’ — that’s their sincerely held religious belief,” the judge said. “How can you tell them, ‘well, we get that, but you can only do it on these days,’ how can that not be a substantial interference?”

Van Meter also argued that Sondag’s statement regarding the church helping someone displaced from their home due to a fire in the middle of the night doesn’t apply to the city’s ordinance since it regulates food service operations.

She also answered the judge’s query by making an analogy to the church operating a 24/7 recovery cafe with a “giant pink neon signs that flashes 24/7.”

“… and that’s part of our decision, our personal decision of how we are going to feed the needy,” Van Meter said, continuing her analogy. “Under the plaintiff’s argument, that has to be allowed even in a residential zone. There is a limit and what the city has been trying to do in various ways for two years, over two years now, is find out … ‘how can we work together so you can continue your meal services?’”

In his argument on behalf of the U.S. Department of Justice’s statement of interest, Lapertosa said Brookings’ ordinance imposes a substantial burden because it affects interstate commerce. He pointed out that members of Smith River United Methodist Church travel across the California-Oregon border to staff one of the four meal services hosted at St. Timothy’s.

“Alleviating that substantial burden would obviously affect interstate commerce by allowing those volunteers to continue that service,” he said. “And I would add that just because people from other churches are coming in … that doesn’t mean that is not fully part of St. Timothy’s religious exercises because it’s actually hosting that activity. Churches do that all the time.”

Lapertosa also argued that the Brookings city code doesn’t define what a restaurant is. They took that definition from the Oregon health codes applying to commercial kitchens. However, he noted that there are other conditional land uses in residential zones that have commercial kitchens that fall under the state’s broad definition of what a restaurant is. These include hospitals with cafeterias, country clubs and nursing homes with dining rooms as well as bed and breakfasts, Lapertosa said. In those cases, he said, serving meals is an allowable use of property in a residential zone.

Under Brookings’ benevolent meal service ordinance, since it’s just churches providing those services, they’re required to apply for a separate permit over and above their conditional use permit to operate their church at all, Lapertosa said. The ordinance’s restrictions on the number of days or hours those meals can be provided only applies to churches, he said.

Before the City Council adopted the ordinance, St. Timothy had a reasonable expectation that they could continue to serve meals just as they had been doing since 2009, Lapertosa argued. The city hadn’t put the church on notice that its meal ministry was a prohibited activity, he said.

“There is no way that St. Timothy’s could have predicted that Brookings was, first going to force them to become licensed through the Oregon Health Authority as a restaurant,” Lapertosa said, “and then turn around and use the same definition of restaurant, saying that you’re actually prohibited operating this use in a residential neighborhood.”

In his closing remarks, Clarke acknowledged that arguments from both sides raise important issues. He said he would review both sides’ comments as well as the briefings and records and “get at it.”

CLICK TO MANAGE